A Quick Math Tour of Variational AutoEncoders

This post serves to introduce and explore the math powering Variational AutoEncoders. A link for the notebook implementation of the discussed concepts in TensorFlow along with explanations has been inserted at the end. I intend for this to be the first in a series of posts on generative models

Neural nets are, if you haven’t figured out yet, just approximations of functions. With mild constraints on choice of activation functions, it is not difficult to prove that neural nets are universal function approximators. This essentially means that a neural network with a single hidden layer containing a finite number of neurons can approximate continuous functions on bounded subsets of $R^n$. These seemingly all-powerful machines are but a bunch of high school math concepts elegantly put together. In fact, most of current pioneering deep learning research focuses less on obtaining a bunch of extra compute power to achieve a $0.2\%$ increase on current state-of-the-art models and more on developing these crazy ideas and understandably so.

Variational AutoEncoders (henceforth referred to as VAEs) embody this spirit of progressive deep learning research, using a few clever math manipulations to formulate a model pretty effective at approximating probability distributions.

Preliminaries

Stacked AutoEncoder

Source : lilianweng.github.io

Source : lilianweng.github.io

If you’re used to staring at architecture diagrams of deep convolutional networks, this should be much easier on the eye. A stacked autoencoder (or just an autoencoder) takes in some input, develops its own representation of it, and attempts to reconstruct the output from its own representation. Formally speaking, given input $\mathbf{x}$, the encoder computes a lower dimensional representation $\mathbf{z} = g_\phi(\mathbf{x})$ and the decoder computes $\mathbf{x’} = f_\theta(\mathbf{z})$, where $\phi$ and $\theta$ are the parameters of the encoder and decoder respectively.

The network is trained to improve its reconstruction ability, and this means our objective function and hence our loss function is just plain old MSE.

But what does it do again? What’s the point in taking some input and making a network learn a condensed representation only to try and reconstruct the original input? The answer is pretty evident - we are building an end to end data compression tool. Train it to convergence and separate the encoder and the decoder, and we have ourselves a compressor and its corresponding reconstructor. But perhaps more importantly, we have the foundation for the brilliant formulation of the VAE.

KL Divergence

A notion of difference between probability distribution is a driving point for research in the domain of generative modelling and is perhaps the most notable differentiator of generative methods. The Kullback-Leibler (KL) divergence is such a metric used in the VAE. For discrete probability distributions $P, Q$, the KL divergence is given as

Hence for every point $x$ such that $P(x) > 0$ (also called support of $P(x)$), this term is a measure of the vertical similarity of the two distributions. It is easy to see that $D_{KL}$ is not commutative and always nonnegative.

Suppose we have two multivariate normal distributions ($d$-dimensional vectors such that each element follows a normal distribution) $p(\mathbf{x}) = N(\mathbf{x}, \mu_{1}, \Sigma_{1})$ and $q(\mathbf{x}) = N(\mathbf{x}, \mu_{2}, \Sigma_{2})$ where $\mu_{1}, \mu_{2}$ and $\Sigma_{1}, \Sigma_{2}$ are the mean vectors and covariance matrices respectively, we have a simplified expression for the KL divergence

That was quite a handful. I have included a crude derivation of the equation below, feel free to skip it if you’re not too comfortable with the linear algebra involved.

Deriving the expression for KL divergence of multivariate normal distributions The multivariate normal distribution $P(x)$ can be given as

Taking the logarithm of the expression, we have

Similarly the other multivariate normal distribution $Q(x)$ can be expressed as

Now, using the original expression for $D_{KL}$ and the formula $\log{A/B}=\log{A}-\log{B}$, we have

Substituting the values we just obtained for $\log{P(x)}$ and $\log{Q(x)}$,

Consider the last term of the expression

Now, an implication of the trace expectation trick gives us a simple simplification

Proceeding similarly after replacing $\mu_2$ with $\mu_2-\mu_1+\mu_1$ in the second term of the equation, we get the terms $tr(\frac{\Sigma_2^{-1}\Sigma_1}{2})$ and $(\mu_1-\mu_2)^T\Sigma_2^{-1}(\mu_1-\mu_2)$, which when added to the last term, yields the required expression

I trust that the reader is familiar with the concept of conditional probability and if not, here’s a refresher.

Variational AutoEncoders

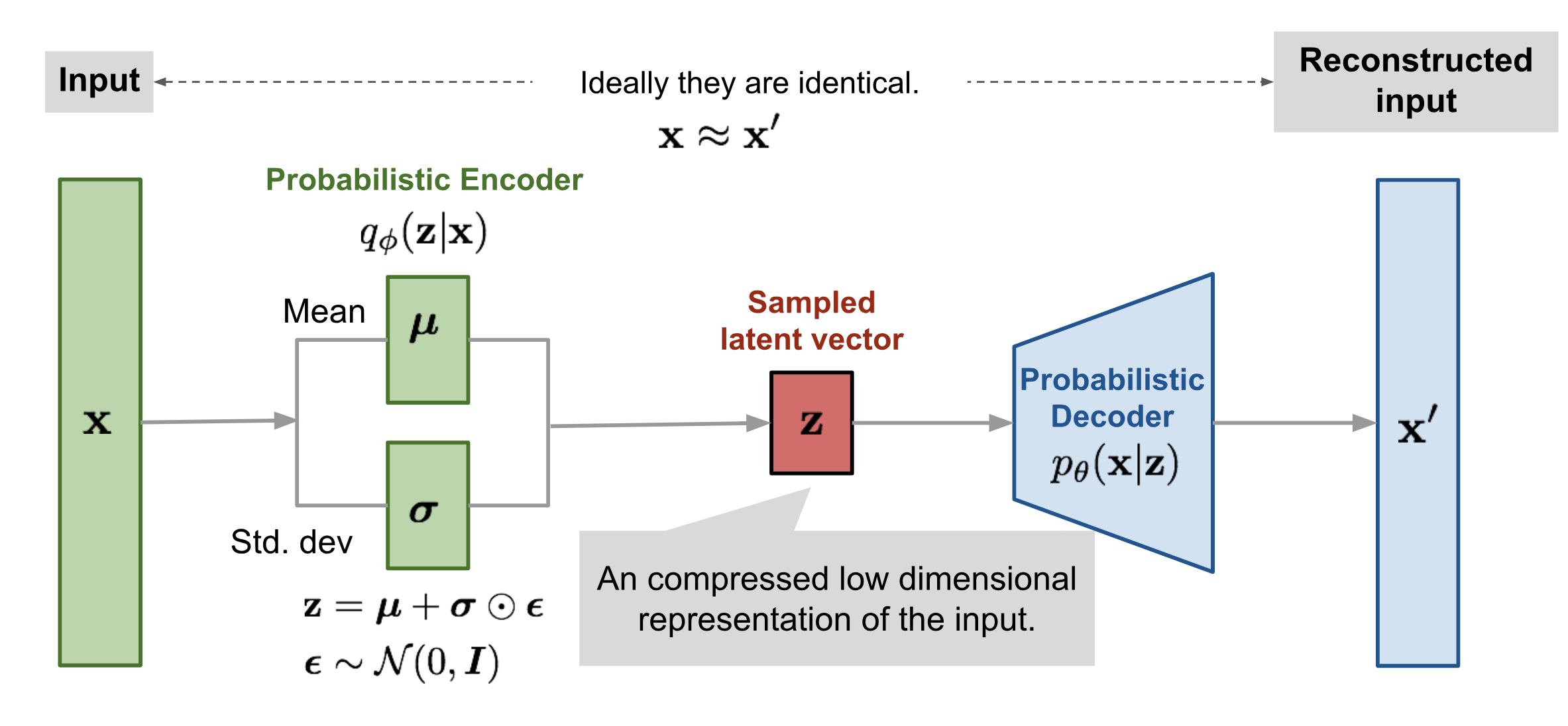

Before we dive into the math powering VAEs, let’s take a look at the basic idea employed to approximate the given distribution. Source : lilianweng.github.io

Source : lilianweng.github.io

The architecture looks mostly identical except for the encoder, which is where most of the VAE magic happens. We have established that stacked autoencoders don’t have much significance in the domain of generative modelling, but a simple modification to the encoder function to infer probabilistic representations of the latent variables as opposed to exact values enables the generation of new datapoints. What this means is that we essentially train the network to learn multivariate normal distributions instead of a fixed vector to represent the encoding. The latent vector is sampled from the learned probability distributions and fed to the decoder.

For instance, assume that in a stacked autoencoder trained on MNIST, the latent vector $\mathbf{z}$ is $3$ dimensional with each of the dimensions representing input features such as stroke width, angle of inclination, presence of a circle, or just about any other learnable parameter. The decoder is trained to take this vector and map it back to the same input. However, instead of feeding these values, we could train the network to recognize values in the vicinity of these and map it back to similar images. We learn normal distributions for each of these features and sample a point from each to generate $\mathbf{z}$, which we then feed to the decoder network. We use the $\mu$ and $\sigma$ modules of the network to represent these distributions.

Loss function

Let’s review the fundamental problem of generating the latent representation $\mathbf{z}$. We wish to obtain a distribution $p(\mathbf{z}|\mathbf{x})$ that would probabilistically infer $\mathbf{z}$. Using simple conditional probability, we have

where

by the theorem of total probability. However, this is an intractable computation as in practice, the dimensionality of $\mathbf{z}$ makes the integral increasingly complex. For example, if $\mathbf{z}$ is $5$ dimensional, we would have $5$ integrals, making the distribution hard to calculate. We instead use Variational Inference (VI) to approximate $p(\mathbf{z}|\mathbf{x})$ using $q(\mathbf{z}|\mathbf{x})$ such that $q(\mathbf{z}|\mathbf{x})$ is a tractable function which is in our case, a Gaussian. Now, how do we determine how good our approximation is? By simply using the concept of KL divergence discussed above. We would like $D_{KL}(q(\mathbf{z}|\mathbf{x})||p(\mathbf{z}|\mathbf{x}))$ to be as small as possible to ensure our approximation is close enough.

The term $p(\mathbf{x})$ can be moved out of the expectation as it does not depend on $\mathbf{z}$

This represents our loss function, where the first term represents the reconstruction likelihood and the second penalizes deviation of $q$ from the prior distribution $p$

The KL divergence term above acts as an inherent regularizer, ensuring a degree of control while training.

Optimization

The optimal network parameters $(\theta^{*},\phi^*)$ are given by

Employing the paradigm of alternate optimization illustrated below, we encounter a problem. To carry out alternate optimization, we first find $\theta^*$

Given $\theta^*$, we proceed to find an estimate for $\phi^*$

We recursively plug in this value of $\phi^*$ in the previous equation to obtain $\theta^{**}$ and so on, for a fixed number of iterations. Recall the loss function given by

In the second step of alternate optimization, we are required to find $\phi^*$ by calculating the required partial derivative after plugging in $\theta^*$. However, consider this derivative

In similar scenarios, it might be standard practice to move the derivative inside the expectation expression. But here, the expectation stochastically draws on samples generated from $q_\phi$. This complicates things as we cannot backpropogate through such a random sampling. If we could rewrite the expectation term such that there is no sampling based on $\phi$, this complication could be circumvented.

This is done using what has come to be known as the reparametrization trick. We make the transformation

such that $\mathbf{z}$ can be represented by a linear transform $\mathbf{z}=g_\phi(\epsilon,\mathbf{x})$ with $\epsilon \sim N(0,1)$. We specifically choose the transform $\mathbf{z}=\mu_\phi(\mathbf{x})+\epsilon\times\Sigma_\phi^{\frac{1}{2}}(\mathbf{x})$, which is a standard transform to convert a unit gaussian to one with a specific mean and covariance.

Let us go over the workflow once more. In the training phase, the network learns to estimate the latent variables through probabilistic distributions. A latent vector $\epsilon$ is now sampled from $N(0,1)$, which was the point of our reparametrization trick. This sampled vector is then converted back to $\mathbf{z}$ using the linear transform described above and fed to the decoder $p_\theta(\mathbf{x}|\mathbf{z})$ to reconstruct the input.  Source

Source

Here’s an illustration of the benefit of reparametrization. While calculating $\nabla_\phi$, the network goes through the random node in the original case, losing differentiability. However, by replacing stochasticity of z by introducing $\epsilon$, we have a workaround to the problem.

Takeaways

VAEs constitute one of the harder concepts to follow for anyone foraying into deep learning. Although the GAN-driven generative modelling domain seems to be achieving constant unprecedented breakthroughs, the importance of the VAE is still widely understated. GANs tend to be much more finicky learners than VAEs, and with the level of abstraction going on, it can often be hard to trace the root of the problem. Here’s a link to my end to end implementation of a VAE on MNIST with (briefer) math explanations. If some of the concepts here were unclear, you might find my alternate explanations there more helpful.